American Irish Historical Society Inc

A national center of scholarship & public education. Home of the transatlantic Irish experience celebrated in lectures, concerts, exhibitions & plays #AIHSNYC The American Irish Historical Society records, celebrates, promotes and reflects the contributions made to America by people of Irish descent. Our motto is "That the world may know." TO ENCOURAGE AND PROMOTE HISTORICAL RESEARCH RELATING TO AMERICANS OF IRISH DESCENT.

Founded

1897

4700

X (Twitter)

2469

Address

New York City

American Irish Historical Society Welcome to the American Irish Historical Society Upcoming Events Great Hunger Sculpture Exhibition January May Monday Friday 1pm Karan Casey Trio in Concert Saturday March 1st 7. 30PM Bread or Blood The Great Hunger in a Kerry Town Monday March 3rd 600PM American Irish Historical Society 991 5th Ave New York NY 10028 Phone 212 288 2263 Disclaimer The views expressed in presentations made at the AIHS or at events held in the AIHS are those of the speaker and not necessarily of AIHS or its Board of Directors. Presentations at AIHS events or the presence of other associations in the AIHS do not constitute an endorsement of the vendor or speakers views products or services. Join Our Mailing List Sign up with your email address to receive news and updates.

From Social media

News about from their social media (Facebook and X).

#OnThisDay in 1919, the Limerick Soviet commenced a general strike in protest against English militarism in Ireland. For three weeks in April, the city's Trades Council took over the entire running of the city, published their own newspapers and even issued their own currency. The Soviet received worldwide publicity and was seen by the British government as a major threat to their power in Ireland, coming as it did in the early stages of the War of Independence.

Like Comment

Data about organisation

Similar organisations

Similar organisations to American Irish Historical Society Inc based on mission, location, activites.

Studying, Collecting and Preserving the Historical Records, Traditions and Relics of Holliston and its People for over 100 Years.

The Eliot Historical Society is a non-profit cultural organization dedicated to the preservation of Eliot's history and education.

Similar Organisations Worldwide

Organisations in the world similar to American Irish Historical Society Inc.

THE IRISH GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH SOCIETY (uk)

Founded in 1936, the IGRS is Britain & Ireland’s largest society dedicated to Irish genealogy.

We are a registered charity founded in London in 1974.

The Irish Literary Society was established in London in 1892.

IRISH DIASPORA FOUNDATION (uk)

Rooms: 100 ppl Ulster Gallery 180-270 ppl Munster Hall 50 ppl Leinster suite 20 ppl Connaught room Email: bookings@iwhc.

Interesting nearby

Interesting organisations close by to residence of American Irish Historical Society Inc

American Irish Historical Society Inc

The American Irish Historical Society records, celebrates, promotes and reflects the contributions made to America by people of Irish descent.

The Holland Society is a historical and genealogical society founded to collect and preserve information respecting the early history and settlement of New Netherland by the Dutch.

Similar social media (7169)

Organisations with similar social media impact to American Irish Historical Society Inc

67453. International Remote Viewing Association

IRVA is a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting the responsible use and development of RV.

67454. Foundation for the Cleveland Public Library

The Cleveland Bradley County Public Library provides informational resources, programs, and services for the personal enrichment, education, and enjoyment.

67455. American Irish Historical Society Inc

The American Irish Historical Society records, celebrates, promotes and reflects the contributions made to America by people of Irish descent.

67457. Greater Cheyenne Foundation

1 Depot Square 121 West 15th Street Cheyenne, WY 82001 Phone: 307-638-3388 Fax: 307-778-1407.

Join us and make a difference for the future!

Sign Up

Please fill in your information. Everything is free, we might contact you with updates (but cancel any time!)

Sign in with GoogleOr

Good News

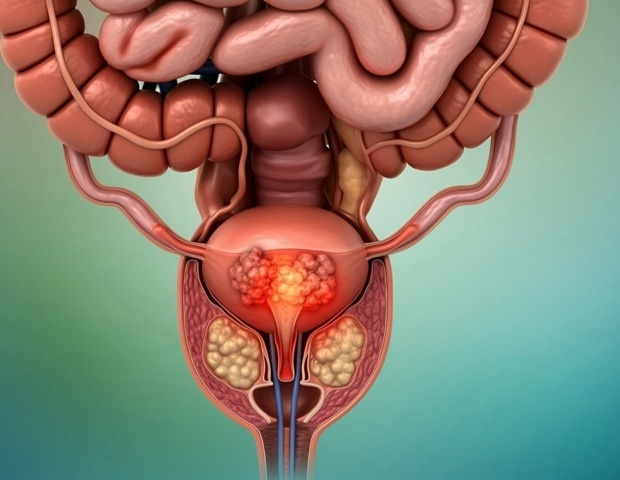

Amazing news for prostate cancer patients! A new combination therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of death by over 40%—hope is on the horizon! #CancerResearch #Hope #HealthInnovation

Breakthrough combo therapy lowers death risk in recurrent prostate cancer

News-Medical.net

Like Comment💖 Thrilled to see the Marat Daukayev School of Ballet dancing in pink this October! Their support for breast cancer awareness is a beautiful reminder of community strength and compassion. Together, we can uplift warriors like Miss Allison! #BreastCancerAwareness #DanceForACause

Column: Dancing in Pink: Marat Daukayev Ballet stands with breast cancer warriors

Los Angeles Times

Like Comment